Sunday, January 21, 2018

Third Sunday After Epiphany

Kalaupapa Sunday

"Follow Me"

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

Jonah 3:1-5, 10 & Mark 1:14-20

On May 12, 1858, a man named S.W. Nueku was licensed to preach here in this church, known at the time as Honua’ula later as Keawakapu and later still in 1944 as Keawala’i. Nueku was licensed by a Clerical Council that met in Lāhainā that day. Historical records noted at the time that “it is hoped that he will, ere long, be ordained as pastor of the church at Honuaʻula” (He Moʻolelo ʻĀina no Kaʻeo me Kāhi ʻĀina E Aʻe ma Honuaʻula O Maui: A Cultural-Historical Study of Kaʻeo and Other Lands in Honuaʻula, Island of Maui, Kumu Pono Associates LLC, Kepā Maly & Oanaona Maly, December 27, 2005, page 65).

In the years that followed, Nueku continued to preach in this church and each year he filed a report that was sent to what was then known as the Hawaiian Evangelical Association, an association of the congregational churches that were established throughout Hawaiʻi. By May of 1861, he was listed as the Assistant Pastor of this church.

It was during his tenure here at Keawalaʻi that the first group of patients diagnosed with Hansenʻs disease were sent to settlement at Kalawao on the Makanalua Peninsula of Molokaʻi. The removal of those afflicted with the disease came through the establishment of a law in 1865 that led to the first settlement at Kalawao.

Of the nine men and three women who were first sent to the peninsula on January 6, 1866, three would go on to become founding members of Siloama Church or The Church of the Healing Spring (Adjourned with a Prayer: The Minutes of Siloama & Kanaana Hou Churches, Kalawao & Kaluapapa, Molokai, 1866-1928, Henry P. Judd, Carol L. Silva & Anwei Skinsnes Law, Ka ʻOhana O Kalaupapa, 2011, page 7).

Of the nine men and three women who were first sent to the peninsula on January 6, 1866, three would go on to become founding members of Siloama Church or The Church of the Healing Spring (Adjourned with a Prayer: The Minutes of Siloama & Kanaana Hou Churches, Kalawao & Kaluapapa, Molokai, 1866-1928, Henry P. Judd, Carol L. Silva & Anwei Skinsnes Law, Ka ʻOhana O Kalaupapa, 2011, page 7).

Later that year on June 12, 1866 action was taken at the ʻAha Paeʻaina or annual meeting of congregational churches in Honolulu to release 12 women and 23 men from their former congregations to form the first church at Kalawao. During the Makahiki season that followed in the month of October that year, the Rev. Anderson O. Forbes was elected as the church’s regular pastor, although he would not live at Kalawao.

Two days before Christmas, Rev. Forbes and the now Rev. S.W. Nueku would make the journey down the trail to Kalawao for the official organization of the church. Kahu Nueku served the church as its Associate Pastor from 1866 to 1874.

Over time his name disappeared from the records and there is no written record to indicate that he returned to us here at Keawalaʻi or if he fell ill to the disease and died in Kalawao. Whatever the case may, Kahu Nueku’s life of service reminds us that some of the patients who were sent to Kalawao and then to Kalaupapa were accompanied kōkua or family members who also lived lives of service in caring for their husband or wife, son or daughter, and other family members who were afflicted with the disease. Many came from our Kalawina or congregational churches.

Two of the patients - Helehewa and Kauhiahiwa - came from our church here in Mākena (Op. cit., pages 148-149). Today we commemorate their lives, Kahu Nueku’s life and the lives of the other men, women and children who were sent into exile to Kalawao and Kalaupapa.

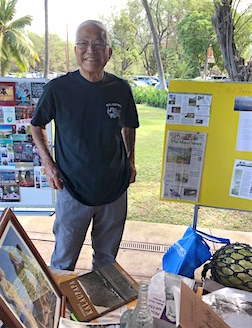

There is a story that appears in a recent issue of The Friend, a publication of the Hawaiʻi Conference – United Church of Christ which claims to be the oldest newspaper west of the Rocky Mountains, founded in 1843. I want to share that story with you this morning keeping in mind that it is only one of 8,000 stories.

“For most of his life, Stan Chong was unaware of a reality that has forever tied his heart and family to a painful time in Hawaiian history. Some 15 years ago, the longtime member of Nuʻuanu Congregational Church, [a sister or partner church to us here at Keawalaʻi], discovered that his grandfather, Fung Tung Shu, was seized by health authorities [on] Hawaiʻi island upon suspicion of Hansenʻs disease in 1923.

Tung Shu was exiled to the remote Kaluapapa (sic) [or what we now know as the Makanalua peninsula] on Molokaʻi, where he and an estimated 8,000 others lived and died in isolation. His fatherless family was destitute and would have starved if not for the kindness of neighbors.

In the early 1900s, families associated with Hansen’s Disease were shunned by society. As a result, Tung Shu’s story was kept secret for decades. ‘It wasn’t something talked about in our family,’ Stan said. ‘My mom never knew her father and she never spoke of him. It must have been too painful.’

Stan remained unaware of his grandfather’s story until his aunt was interviewed by a relative for a family history project. He discovered that Tung Shu may never have contracted Hansen’s disease – at least not prior to living in Kalaupapa. He blew off his right hand and lost an eye while dynamite fishing in 1910, leaving him disfigured and easily mistaken as afflicted.

[Last] summer, over 15 years after realizing his grandfather was buried at Kalaupapa, Stan and his sister organized a pilgrimage to visit Tung Shu’s grave and pay their respects.

‘It was very uplifting to find my grandfather’s grave,’ he said. ‘I feel fortunate that his grave is marked so that we could locate it; someone had enough aloha for him to do that.

Interestingly, Tung Shu is buried in one of Kalaupapa’s Hawaiian cemeteries, not its Chinese cemetery. Stan speculates that his Hawaiian-speaking grandfather could not afford to pay dues to the Chinese Burial Society, so one of Kalaupapa’s patients – 90 percent of whom were Native Hawaiian – marked his grave with a concrete slab and lava rock” (The Friend, Hawaiʻi Conference – United Church of Christ, Volume 33, Issue 5, December 2017, page 5)

Almost fifty years separates the days for which Kalawao and Kalaupapa was home for Kahu Nueku and Tung Shu. As Stan Chong discovered, his grandfather may have been sent there by mistake. As for Kahu Nueku, the journey to Kalaupapa was one that he took of his own volition.

Our lectionary readings this morning from The Book of Jonah and The Gospel According to Mark may seem like an unlikely pairing as we commemorate the lives of those who lived and died on the peninsula during those years of exile. There is a strong case to be made in both readings that there is a call to repentance – a turning away from what one has done or not done.

The prophet Jonah was reluctant to preach repentance to the Assyrians living in Nineveh. We remember Jonah because of the story of how he was swallowed by a great fish as he attempted to escape his role of emphasizing God’s persistence in seeing that the task to which he was called was carried out.

In our reading, Jonah is still hesitant about fulfilling the obligation to which God called him. However, Jonah eventually goes to Nineveh. When he proclaims to those living in the city that Nineveh will overthrown, destroyed in forty days, the people believe Jonah’s proclamation and begin to show signs of their remorse by fasting and wearing garments of coarse cloth.

The people repent and remarkably God also repents (Amos 7:1-4). All of this makes for a great fish story, but one could hardly proclaim to the patients who were exiled to Kalaupapa that they needed to repent, assuming as did some in the church at the time, that they did something wrong, that they must have sinned and their disease was a punishment for their sins.

Repentance is not simply to turn away from one’s wrongdoing or sin. Repentance is about turning turn toward God fully trusting in the good news of God’s mercy, grace and love. If that is the case, then we are all in need of repentance. The call of Simon, Andrew, James and John is a call to such a repentance but it is also a call to a radical discipleship – a discipleship of leaving property and family in response to Jesus’ invitation: “Follow me” (Mark: 1:17).

In the midst of their own suffering, the patients chose to turn to Ke Akua. A plaque dedicated in 1952 appears on the inside wall of Siloama Church. It lists the names of men and women who established the church in 1866 along with the following words: “Thrust out by mankind (sic), these 12 women and 23 men, crying aloud to God, their only refuge, formed a church. The first in the desolation that was Kalawao.”

Over the years, I have had two opportunities to visit Kalaupapa – once alone on a silent retreat and on another occasion with our members of our choir to celebrate the anniversary of the founding of Siloama Church. It was on the second visit that we met Paul Harada, the brother of Uncle Taka Harada, a member of our church.

Paul was sent to Kalaupapa from their home at Lumahai Valley on the island of Kauaʻi when he was a boy. Uncle Taka was still a boy, himself, when he met his brother Paul for the first time. In the years that followed their reunion, they began to see each other and to spend more and more time together.

Paul was sent to Kalaupapa from their home at Lumahai Valley on the island of Kauaʻi when he was a boy. Uncle Taka was still a boy, himself, when he met his brother Paul for the first time. In the years that followed their reunion, they began to see each other and to spend more and more time together.

I remember commenting to Uncle Taka one day during our stay at Kalaupapa how excited patients may have been about fishing in the waters surrounding the peninsula. “It must have been great fishing,” I said.

But he reminded me that many of the early patients were unable to fish because of the effects of the disease. Fingers, hands and feet became stumps.

I thought about Kahu Nueku and how he responded to Jesus’ invitation: “Follow me and I will make you fishers of people” (Mark 1:17). The call to serve was clear for him as it was for Simon, Andrew, James and John.

In 2009, President Barrack Obama signed into the law The Kalaupapa Memorial Act. The act authorizes the advocacy group Ka ʻOhana O Kalaupapa to erect a memorial that will list and preserve the names of those who lived and died as patients.

Valerie Monson, a former journalist for The Maui News and Executive Director for Ka ʻOhana O Kalaupapa said, “We now have a digital archive with information for about 7,000 people.” In June 2017, the 195th ʻAha Paeʻaina of the Hawaiʻi Conference – United Church of Christ unanimously passed a resolution at its annual meeting that was held here on Maui encouraging churches members to support “The Kalaupapa Memorial” by making donations toward its completion for the benefit of future generations.

At their December 2017 meeting, the Board of Trustees of this church approved the release of $1,000 for the memorial from a gift that was received from an anonymous donor. If you would like to match any portion of that gift with your own gift, you may do so by indicating that your cash gift or check is for the Kalaupapa Memorial.

“My family lives in many places now,” said Stan Chong, “mostly on Oʻahu and [in] California, but even as far away as Japan. A large piece of our heart and of our ʻohana will always be with our grandfather at Kalaupapa.”

Let it be said on this day that a large part of our hearts and the hearts of our church ʻohana will always be with Kahu Nueku, Helehewa, Kauhiahiwa and the thousands for whom the settlement was home. We join our voices today with the psalmist and with the men, women and children of Kalawao and Kalaupapa in proclaiming: “Trust in God at all times, O people; pour out your heart before God; God is a refuge for us” (Psalm 62).

Helen Keao, a member of Kanana Hou Church was sent to Kalaupapa in 1942. She said, “I have read and I have heard many stories about Kalaupapa and of the people that lived at Kalawao – that the people who lived here were bad, that the land was without law and the people were lawless, immoral and they were engaging in a lot of wickedness. But, I don’t think, in fact, I don’t believe all the people were bad because I feel if that was true, then there would not be a church called Siloama, which was the first church to be built here at Kalawao” (Adjourned with a Prayer: The Minutes of Siloama & Kanaana Hou Churches, Kalawao & Kaluapapa, Molokai, 1866-1928, Henry P. Judd, Carol L. Silva & Anwei Skinsnes Law, Ka ʻOhana O Kalaupapa, 2011).

Amen.