Kahu's Mana‘o

Sunday, June 3, 2018

"They Were Silent"

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

Mark 2:23-3:6

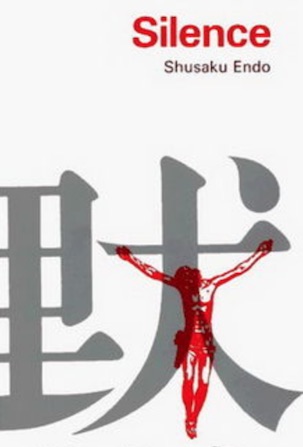

Shusako Endo was born in Tokyo in 1923. He was a much-decorated Japanese writer. He received the Tanizaki Prize in 1966 for his novel Silence, a novel that has been called his “greatest achievement” (“Shusaku Endo’s Silence,” Luke Reinsma, Seattle Pacific University, Volume 27, Number 4, Autumn 2004) and “one of the twentieth century’s finest novels” (“We Have Never Seen His Face,” Brett R. Dewey, Center for Christian Ethics, Baylor University, 2005)

I became familiar with Endo’s name and with his novel over forty years ago while I was a student in seminary. In Silence, “the mystery involves a controversial historical figure, Cristovao Ferreira, a Jesuit provincial who worked for three decades in Japan before” he reportedly renounced his Christian faith.

I became familiar with Endo’s name and with his novel over forty years ago while I was a student in seminary. In Silence, “the mystery involves a controversial historical figure, Cristovao Ferreira, a Jesuit provincial who worked for three decades in Japan before” he reportedly renounced his Christian faith.

Some who knew him refused to believe the report. A group sought and was given permission to set sail from Lisbon, Portugal to Japan to discover what happened and to provide support for those who were being persecuted as well as to provide support for a dwindling number of priests.

Among the group was Sebastion Rodrigues, a fervent priest who was a character who was also based on a historical figure. He arrived in Japan in 1639 along with other companions. By the time of his arrival, the Christian population has been driven underground.

In order for security officials to ferret out those who may be Christians, the people who were suspect were forced to trample on a fumi-e or a carved image of Jesus as a renunciation of their faith. If they refused, they were tortured and put to death.

Upon his arrival, Rodrigues is captured and forced to witness the brutal torture of Japanese converts, a process that will cease only if he steps on the fumi-e himself. Rodrigues understands suffering for the sake of one’s own faith, but he struggles over whether or not it is self-centered and unmerciful to refuse to trample on the fumi-e to end another’s suffering.

What he sees horrifies him and he questions the silence of God in such suffering. But a moment comes when he looks upon a fumi-e and Christ breaks his silence:

I more than anyone know of the pain in your foot.

You may trample.

It was to be trampled on by men (sic)

That I was born into this world

It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.”

Silence was adapted into a film that was released two and a half years ago. It was directed by Martin Scorsese. It premiered at the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome on November 29, 2016.

In a review of the film, Dr. Lloyd Sederer, a psychiatrist and public health doctor, recalled meeting Father William Johnston, an Irish Jesuit at Sophia University in Tokyo, who translated Silence into English. Father Johnston made a distinction between Jesus and the institutional church.

He wrote, “It was the love derived from faith in Jesus that the early Japanese Christians seem to have achieved. That too, was what Rodrigues came to realize, his epiphany: It was not [the] doctrinal requirements and duties [of the institutional church] but the personal love of Christ that was necessary for him to save others, and in so doing preserve his authentic faith” (“‘Silence’: Directed by Martin Scorsese from the Book by Shusaku Endo,” Lloyd I. Sederer, HuffPost, January 18, 2017).

Such a moment comes in Jesus’ conflict with the religious leaders of his day. In our reading from The Gospel According to Mark we find ourselves in the midst of two disturbing incidents that occur on the Sabbath – a day meant for religious observances and abstinence from work.

Doctrinal requirements and rules become religious rules and regulations that religious leaders conclude have been violated when Jesus’ disciples walking through a wheat field pick grain for eating and when Jesus heals a man with a crippled hand. Eyebrows and questions are raised by the Pharisees and by Jesus.

Jesus makes his point clearly in two instances. First, by saying to the religious leaders, “The Sabbath was made for humankind, not humankind for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27) and second, when he asks, “Is it lawful to do good or to do harm on the Sabbath, to save life or to kill?” (Mark 3:4).

Jesus is very, very, very angry at the Pharisees for their “hardness of heart” (Mark 3:5). “They were silent” (Mark 3:4), unable to respond to his questions, because they themselves were furious with Jesus. In their hostility against Jesus, they conspired, they colluded with political authorities on how best to destroy him.

Dr. Don Saliers is at Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. He offers the following observation of our reading this morning: “Mark’s Jesus should startle, if not unsettle, us . . . It is so easy to forget the spirit of religious institutions and practices in the attempt to apply regulations with absolute human certainty” (Feasting on the Word, Year B, Bartlett & Taylor, Westminster/John Knox Press, Louisville, Kentucky, 2009, page 96).

That is what Father Ferreira and Father Rodrigues wrestled with in their relationship with the religious leaders in Rome. For their actions to do good, to heal, to save life, they were abandoned by the church.

Dr. Saliers cautions, “To claim divine authority on behalf of the church is itself to stand vulnerably under the living gospel, which is Christ. In every generation [and in every corner of the world] there have been human attempts to invoke the name of God on programs and policies that end up subverting the love and grace shown in Christ” (Op. cit.).

That love and grace is what Father Ferreira and Father Rodrigues demonstrated. The institutional church abandoned them, but they never abandoned their faith in a loving and gracious God.