Sunday, July 19, 2015

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

“Hulihia: What We Reconcile”

Ephesians 2:11-22 &

Mark 6:30-34, 53-56

A stone wall separates two neighbors. In the spring, the two meet as they walk along the wall making repairs. One neighbor sees no need for a wall to be kept – there are no cows to be contained, only apple trees and pine trees. He does not believe in walls for the sake of walls.

The other neighbor resorts to an old adage, "Good fences make good neighbors." The one neighbor who sees no need for a wall is unconvinced and presses his neighbor to look beyond such reasoning. But his neighbor will not be swayed.

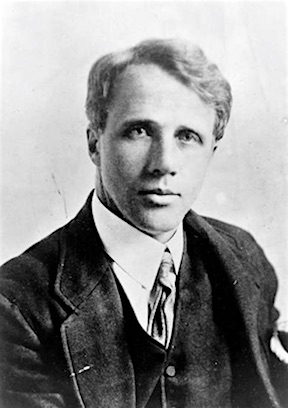

Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) was an American poet who was born in 1874 in San Francisco. He died in 1963 in Boston. His poetry often included realistic depictions of rural life in New England in the early twentieth century.

Robert Lee Frost (1874-1963) was an American poet who was born in 1874 in San Francisco. He died in 1963 in Boston. His poetry often included realistic depictions of rural life in New England in the early twentieth century.

Over the course of his lifetime Frost received four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. His command of American colloquial speech includes a poem about a stone wall separating two neighbors. Among his many writings is “Mending Wall”, a poem that appeared in North of Boston, his second collection of poetry that was published in 1914.

It begins with a familiar line that is often quoted and ends with another familiar line:

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun,

And makes the gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But as spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill,

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls.

We have to use a spell to make them balance;

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him,

He only says, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows?

But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down. I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not let go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

It is said that Frost would often examine complex social and philosophical themes through his poetry. What catches our attention at the heart of “Mending Wall” is how two men who are civil and neighborly decide to build a barrier between them. In some ways their effort seems relatively harmless, whether it is out of tradition or habit.

Yet, it becomes quickly apparent that their attempt to maintain the wall is doomed. Whether at the hands of hunters or elves, or the frost and thaw of winter, the stones fall and tumble again and again.

Frost invites us to consider what it means for us to build barriers; how such barriers are always doomed to fail; and how we persist in building them anyway. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” Sadly, there are places around the world that still have walls and are still building walls and barriers that separate people from one another. We know them well - the barrier between the Israelis and Palestinians built in 2002 is part-wall, part-fence. It measures 403 miles in length.

In 2006, the Secured Fence Act promised 700 miles of fencing, walls and vehicle barriers along the U.S.-Mexico border. In 2012, the U.S. Department for Homeland Security reported the completion of 651 miles of fencing and walls. There are politicians who would have us believe more is needed.

There are other walls. The first wall that was constructed in Northern Ireland was built in 1969 after riots and fires in the western part of the city of Belfast. The most recent wall was built in 2008 and each year on the Twelfth of July the Orange Order Parade takes place to commemorate over three centuries of hostilities.

Over this weekend, around 10,000 marchers dispersed across twelve venues. Trouble erupted as the Protestant marchers passed a group of Catholics near a church. A series of barriers remain between Catholic and Protestant communities.

In 1987, Morocco built a wall that spanned 1,677 miles made with sand and stone, barbed wire, ditches and mile fields along the edge of the Western Sahara desert. It was built as a result of a dispute between the Moroccans and the Sahwari tribal people over land ownership.

In 2007, Iran started construction on a wall along its border with Pakistan to prevent what they say is the movement of black market goods, drug trafficking and illegal immigration. The wall is 435 miles in length and 9 feet high. A tribal group living in both countries have had their communities divided by the wall.

The walls that divide us from one another are sometimes made out of sand and stone, barbed wire and land mines. But the physical walls we build come as a result of the walls we build within ourselves against one another for religious, political, social, and economic reasons that we do not always understand.

We are reminded of that reality in The Letter of Paul to the Ephesians. The letter was addressed to Jews and Gentiles in the early Christian church among whom there was great animosity.

In our reading, a derisive term is used by the Jews to described Gentiles – “the uncircumcised.” It wasn’t just a descriptive term, but a statement meant to make clear that the Gentiles did not quite measure up to being a part of God’s chosen people.

For the Jews circumcision was a necessary act to show that one was a part of God’s covenant. But the letter makes clear that while Gentiles were once “strangers to the covenants of the promise, having no hope and without God in the world” (Ephesians 2:12), it was the sacrifice of Jesus that brought them into the “commonwealth of Israel” (Ephesians 2:12).

It was a commonwealth created, not as a nation state, but as a community of faith. It was a commonwealth based on the life, death and resurrection of Jesus that drew Jews and Gentiles together. It was a commonwealth that was meant to put an end to the racial, cultural and religious animosity between both groups.

But it was also a commonwealth that needed more than changes in the law to address the underlying causes of the discord for between them. For Jews and Gentiles in the early church, a spiritual transformation was needed in order for them to overcome their differences.

Might that be the lesson for all of us today in the aftermath of the shootings that resulted in the deaths of nine members of Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina on June 17, 2015? While many welcomed the action taken by the South Carolina legislature to remove the Confederate flag from the Statehouse grounds on July 10, 2012 and placed in a museum, others were more keenly aware that it would take more than changes in the law to remove a flag to change the hearts and minds of people.

A demonstration by a North Carolina chapter of the Loyal White Knights of the Klu Klux Klan yesterday is an indication there is still much to be done. The wall of hostility remains.

In our reading from Ephesians 2 we are reminded at the outset of God’s unconditional grace, a grace that makes it possible for Jews and Gentiles to be reconciled to one another. Because of Jesus Christ, the dividing wall between them is broken down. No longer are they strangers or aliens to one another but citizens with the saints and members of the household of God (Ephesians 2:19).

It is a household built on the foundation of the prophets who foretold the deliverance of the Jewish people, the apostles who proclaimed Christ’s redeeming love, and the reconciling cornerstone of Jesus himself. Together there is no dividing wall but a spiritual home for all. (Seasons of the Spirit, Seasons/FUSION Pentecost 1 2015, Wood Lake Publishing, Inc., 2014, page 118) Despite our persistence to build barriers between one another - whether we are Jews or Gentiles, Protestants or Catholics, English or Irish, Israeli or Palestinian, Muslim or Christian, Black or White, Moroccan or Sahwari, Iranian or Paskitani –there is something that doesn’t love a wall.

I was living in Berkeley, California when the Berlin Wall was torn down in 1989. A friend was in what was then known as West Germany visiting the divided city of Berlin.

We met not long after she returned home to Berkeley. It was then that she told me about her visit.

As an independent filmmaker, she had traveled to Berlin for a film festival. While there she was able to find the gravesite of her grandmother in a Jewish cemetery. It was a transforming moment for her. But what followed soon afterwards was also a transforming moment. She happened to be in the city on the eve of the dismantling of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

Word had spread quickly throughout the city that an announcement had been made by the East German government that the passages between the East and West were about to be opened. In the commotion that followed, thousands found their wall and began to physically tear down the concrete barrier that had divided the city for almost three decades.

I knew enough of what transpired at the end of World War II when the city was divided into four zones occupied by the U.S., Great Britain, France and what was then the Soviet Union. I knew enough of the history that led to the construction of a barbed wire fence in 1961 and later a concrete wall in 1965. I knew enough that many died attempting to cross from the East to the West.

I knew enough that I was convinced by the observation made by Frost: “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” I was even more convinced when my friend stretched out her arm and opened the palm of her hand and said, “I brought a piece of the wall back for you”, and handed it to me.

I took chipped piece of concrete that had been sprayed with graffiti in shades of blue and purple fluorescent paint. November 2014 marked the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Those who visit the city today say it is hard to believe the wall ever existed.

A few remnants of the wall in its physical manifestation remains. But what also remains is the work of chipping away and dismantling the walls within our hearts and minds. hardened by anger, bitterness and resentment. “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.”

Let us pray: We give thanks, O God, that we are a part of your household as forgiven people and as a people who forgive. We open our hearts and minds to your peace and to your call to be reconciled to one another and to others. Amen.