Sunday, July 1, 2018

Sixth Sunday After Pentecost

Open and Affirming Sunday

"Our heart is wide open"

The Rev. Kealahou C. Alika

2 Corinthians 6:1-13 & Mark 5:21-24, 35-43

When I asked her to describe what happened the day government officials knocked on their door, she paused for few moments as if to collect her thoughts. She recalled being told that they needed to pack a bag of clothes, just one bag or suitcase per person, and that they were going to be taken to the train station in a couple of days. They were told to meet at a certain location, along with others from the surrounding community, in order to be transported to the train station.

Within 10 weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, an executive order was signed by President Roosevelt calling for the removal of Americans of Japanese ancestry – both citizens and resident aliens – from their homes and sent to what some called relocation centers or detention centers and others eventually called internment camps or concentration camps. It was said that the “evacuation” of men, women, and children was a matter of national security.

Within 10 weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, an executive order was signed by President Roosevelt calling for the removal of Americans of Japanese ancestry – both citizens and resident aliens – from their homes and sent to what some called relocation centers or detention centers and others eventually called internment camps or concentration camps. It was said that the “evacuation” of men, women, and children was a matter of national security.

The U.S. military defined the entire West Coast home to the majority of Americans of Japanese ancestry as a military area. Concerned about possible acts of espionage or sabotage, more than 120,000 men, women, and children were relocated to remote camps built by the U.S. military in scattered locations around the country. We know now that during the course of World War II, 10 Americans were convicted of spying for Japan, but not one of them was of Japanese ancestry.

She was a child when the government officials came to their home.

When they arrived at the train station a few days later, she remembered seeing soldiers with rifles. Each man, woman and child was tagged with a number.

“The window shades were all pulled down so you couldn’t see outside,” she said. “We had no idea where we were going.”

“No one spoke. Some were sobbing,” she added, “but there was no talking or any commotion.”

As the train left the station she noticed the worried look on her mother’s face. “She told us not to cry!”

“Shikata ga nai,” others would say. “Nothing can be done about it.”

Along the way the train stopped a few times in the middle of nowhere. They were told that they could relieve themselves alongside the track if they needed to. It was good, she thought, to get out in the fresh air and just stretch her legs a bit.

After what seemed like a long, long journey the train stopped. They had arrived at a place called Heart Mountain in Wyoming, a dry windswept area, and for the next three years, it was home.

The camp at Heart Mountain included 650 military-style barracks that could hold a total of 13,997 detainees. The population peaked at 10,767 making it, at tge time, the third largest town in Wyoming.

Some resisted the incarceration and encouraged other detainees to refuse military induction. But at Heart Mountain, at least 800 Japanese American men joined the U.S. military.

Others enlisted at other camps including my father who was living in Kona at the time. He was among the more then13,000 men of Japanese ancestry who eventually became a part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of the 100th Infantry Battalion.

The Nisei Veterans Memorial Center here on Maui, in Kahului, is dedicated to those who served in the 442nd. The center features a preschool, an adult daycare and educational exhibits on the combat team which became the most highly decorated unit of the war.

It was not until December 1944 that the act that led to the executive order was suspended. The camps were finally all closed down in 1946.

German Americans and Italian Americans were also targeted including 11,000 people of German ancestry and around 3,000 others of Italian ancestry. But the effect on what was essentially the entire Japanese American community residing on the continental U.S. was to have a lasting impact on the lives of those who were imprisoned for three years without trial; this despite the fact that the Munson Report, commissioned secretly in early 1941 by President Roosevelt, ,concluded that the vast majority of Japanese Americans were “loyal to the United States” and that “there will be no armed uprising of Japanese.”

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a ban on travel to the U.S. from seven countries: North Korea, Syria, Ian, Yemen, Libya, Somalia and Venezuela. The ruling came after months of challenges to the president’s executive order on immigration which previously targeted only Muslim-majority countries. The 5-4 ruling from the court was said to be an affirmation of the president’s power over matters of national security.

In the meantime, hundreds of thousands of people in major cities and small towns across the country took to the streets yesterday calling for the reunification of over 2,000 children and parents who were separated over the course of a six-week period in May and June. An executive order signed in June is meant to end the separation of families at the U.S./Mexico border by detaining parents and children together for an indefinite period of time.

While the practice of separating families has ended, the plight of the more than 2,000 children remains. In addition, it appears there are still to keep immigrant families from crossing the border under lock and key.

The Department of Defense announced they have asked the Department of Homeland Security to get ready to hold up to 12,000 people in military facilities or temporary camps on Pentagon property, preferably in Arizona, California, New Mexico or Texas. After a report was leaked last week that the Navy was considering a site at the Concord Naval Weapons Station that was slated to hold up to 47, 000 people, the plan was scrapped.

When I saw photographs of children marching in a line through military-style barracks, I realized how easy it was for a mother with a young daughter to say to her young daugther, “Shigata ga nai. Nothing can be done about it.”

It all sounds familiar. It all feels familiar. It all looks familiar. There is cause for concern.

Long ago, a leader in a synagogue named Jairus came to Jesus and fell at his feet and begged him repeatedly, “My little daughter is at the point of death. Come and lay your hands on her, so that she may be made well, and live” (Mark 5:22-23). So Jesus went with Jairus to his home.

Along the way, they were delayed by a woman who also sought for Jesus to heal her. She did not beg for him to heal. She thought it would be enough for her to just touch the hem of his garment – and it was.

As Jesus and Jairus approached the home where the child was, some of the people came out to them and said to Jairus, “Your daughter is dead. Why trouble Jesus any further?” (Mark 5:35) Shikata ga nai.

But Jesus was undeterred. He allowed no one to follow him except Peter, James and John. When they came to the house, Jesus saw the commotion. The people were weeping and wailing loudly.

“Why do you make a commotion and weep?” he asked. “The child is not dead but sleeping.”

The people mocked him with their laughter as if to say, “There is nothing that can be done here.”

Jesus put everyone out of the house and then went in with Jarius and his wife and Peter, James and John. He took the child by the hand and commanded her, “Little girl, get up!” And immediately she got up and began to walk. She was twelve years of age.

When the government officials came to their home, she was a girl not much older than Jairus’ daughter. After they were released from the Heart Mountain, she moved with her mom and her brother to Skokie, Illinois. Returning to the West Coast was too painful. Unlike the little girl who was immediately healed by Jesus, it would not be until decades later that the long process toward healing would come for her.

On August 10, 1988 President Ronald Reagan made the following comments at the signing of a bill providing restitution for the “Wartime Internment of Japanese-American Civilians”: “ . . . we gather here today to right a grave wrong. More than 40 years ago, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in makeshift internment camps. This action was taken without trial, without jury. It was based solely on race . . . ”

The president then added, the interment was “a mistake.”

Today, other children are being traumatized through no fault of their own.

In his letter to the church in Corinth, Paul reminds us that the work of our ministry is rooted in God’s saving work of reconciliation. It is a ministry that is profoundly experienced wherever there is human hardship and pain. We will come to know that hardship and pain if our hearts are open wide and if our hearts are open wide, we will leave the cynicism of the world behind.

To be sure, we can offer our thoughts and prayers but we must also call on others to open wide their hearts. After all, that is the call to action that the Apostle Paul made to those who were in the church of Corinth.

Paul addressed his letter to “a community that [was] divided, distracted and self-preoccupied, reconciled with neither God nor one another” (Feasting on the Word, Year B, Volume 3, Bartlett & Taylor, Westminster/John Knox Press, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 2009, page158). In many ways, we seem to live in a world and in countries today that are “divided, distracted and self-preoccupied.”

Paul cautioned those in the church in Corinth and he cautions us today that much more is at stake than the pursuit of personal or political gain. He makes clear that God is the source of our life in Christ Jesus (1 Corinthians 1:30). We are who we are solely because of what God has done.

“God’s saving work of reconciliation is first said to encompass ʻus’ (2 Corinthians 5:18), that is, Paul, his colleagues, and doubtless all Christians. But the scope is cosmic, for it is the world as a whole that is the object of God’s reconciling love” (2 Corinthians 5:19).

“Reconciliation means . . . that a relationship of enmity and hostility has been brought to an end, and in its place stands a relationship of peace and goodwill. Yet the initiative for bringing an end to the hostility existing between humanity and God lay with God: ʻall this is from God” (Romans 11:36; 1 Corinthians 8:6)

She was a little girl when they came to her door. They were men she did not know. She was taken away from her home for reasons she did not understand.

It was wrong now.

I know, in the words of the Apostle Paul, that despite “hardships, calamities, beatings, imprisonments, riots, labors, sleepless nights, [and] hunger,” we will commend ourselves in every way “by purity, knowledge, patience, kindness, holiness of spirit, genuine love, truthful speech, and the power of God” to open wide our hearts (2 Corinthians 6:5-7) to all, even to those who would do harm to others by their words and through their deeds.

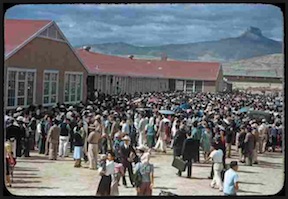

The photo above is from a 2012 NPR.org piece: "A Dark Chapter Of American History Captured In 'Colors'". Quote: "Bill Manbo, an auto mechanic from Riverside, Calif., took these photographs after he and his family were forced to move to a Japanese-American internment camp in 1942, just months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor."