May 26, 2024 – Trinity Sunday

Rev. Gary Percesepe

Isaiah 6: 1-8 & Romans 8: 12-17 & John 3: 1-10

Trinity Sunday is the one Sunday every year when, to paraphrase the poet T.S. Eliot, “we make a raid on the inarticulate.” Trinity Sunday attempts to bring to speech a complex, multifaceted God.

Why can’t things be simpler?

Because in Jesus Christ we discover that God’s rich, relentless love for us is not simple, hence there’s no simple way to speak of it.

Scripture declares, “No one has ever seen God.” God is unfathomable, beyond the reach of our thinking and perceiving.

We know God only as God has revealed God’s self, and Jesus Christ is the first fully realized human being, a complete and sufficient revelation of who God is and what God does. So, if you want to know who God is, look at Jesus. Everything we believe about God flows from there.

This is exceedingly controversial. In his first advent among humans, when Jesus appeared as “God’s Son,” the Messiah—that is, the anointed one of God—all holy hell broke out. Lots of people looked at Jesus, listened to his teachings, witnessed his works, saw his death, and said, Whoa, hold on—Hell no, that’s not God! God is powerful, high and lifted up, God is distant from us, surely God doesn’t look like this guy—I mean, he is short, swarthy, dark skinned—he’s an illiterate Jewish Mediterranean peasant with lots of attitude! Jesus failed to measure up to people’s preconceptions of who God ought to be and how God ought to act.

Has anything changed?

Not really. Modern people want God to be generic, abstract, vague, distant. A God who can’t disturb us or get in our business. A God much like the one we encountered in a philosophy class somewhere: Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, Plato’s conception of the good beyond being, Anselm’s supremely perfect being beyond which no more perfect being may be conceived. A God who exists in the understanding as a big, blurry concept we can manipulate to mean anything we want, someone who looks a little bit like us and acts a little like us, except maybe more so. Like the Greek and Roman gods, mortals elevated to deathless status on Mt. Olympus, retaining their human quirks and faults amplified to a somewhat comical level, Zeus hurling fire bolts, Athena shooting arrows at her enemies, Poseidon roiling the waters, Mars launching wars. Just like us, only more so.

Jesus of Nazareth would never qualify as a Greek or Roman God. God got too physical, too explicit, too peculiar; but mostly, God in Jesus got too close for comfort. Isn’t that what’s happening in the bizarrely comical conversation Jesus has with a religious leader? Jesus got all up in Nicodemus’ face and challenged him. We can almost hear the steam escaping Nicodemus’ brain and hear his silent objections: God is not supposed to treat me like this. God is not being nice! Doesn’t this man know who I am? God would not dis me like this, this cannot be God. He talks in riddles. He has an attitude. He’s not it.

Many moderns think of God as a polite deity, vaguely benevolent with elegant manners, kind of a cross between Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart, with a dash of George Cloony thrown in, salt and pepper hair, definitely White; all the women love him, all the men want to be like him.

We feel threatened by a God who shows up where we live. We’ve designed the modern world to be controlled by us, functioning nicely by itself thank you very much, everything clicking along following natural laws, harnessed to magnificent human technologies. Who needs a God to show up and actually do stuff, especially controversial stuff, saying embarrassing things like, the hookers on this island are going into heaven ahead of you church folk, you brood of vipers, sell all that you own and follow me, he that is first shall be last and the last shall be first, let the dead bury the dead, and whoa, nelly!

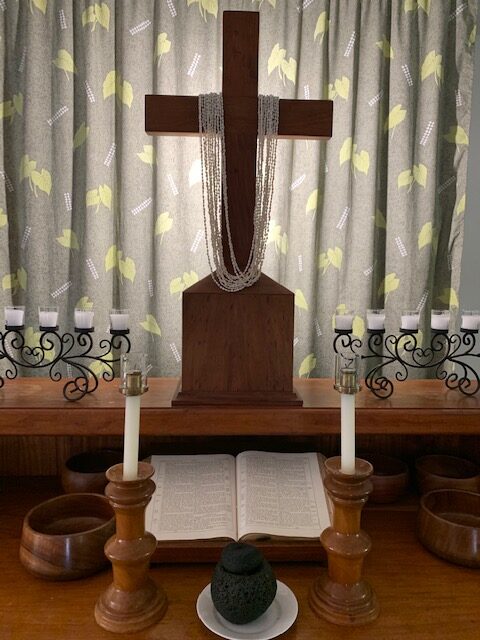

The deistic God of the philosophers is about all we can take: a non-invasive inactive, minimalist, detached, silent God who does our bidding. There’s a reason why thoughtful modern people seem determined to sever Jesus from the Trinity, to make him a fascinating and wonderful moral teacher, a really nice person who enjoyed lilies and birds and was kind to children and people with disabilities. Come to think of it, kind of like our Dashboard Jesus here, someone entertaining for one hour on Sunday; someone we can control and put back into the box whenever we feel like it.

The Trinity is the exact opposite of Dashboard Jesus. You can’t control God. God can’t be put in a box. There’s nothing safe about the Trinity. You know, I put Dashboard Jesus up here on the pulpit on February 25th, thinking when the time was right, when we finally grasped the absurdity of the American consumer God we could take him down, maybe around Easter; he was good for a laugh in February, but the joke was over. But lately I’ve become convinced that American Christians still feel we can control God, maybe make him a bit more nationalistic, a Proud Boy to assure real Americans that they won’t be replaced by those Other people; we seem to prefer a plastic Jesus made in our own image to a real God who visits us to make demands on our time, attention, and especially our resources. The real Jesus talked more about money than sex and didn’t wear an American flag decal or run for office.

It would be a whole lot easier to be Unitarian, wouldn’t it? It’s easier on the brain and the conscience, not to mention the intellect, one reason former Congregationalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson and the New England Transcendentalists abandoned ship. The problem is that once we discovered that “God was in Christ” things got complicated—turns out God was more demanding and much more interesting than we had first thought: a God who created us unique from every other person yet challenges us continually, who provokes us, a God who actually pursues us and won’t leave us alone, a God who keeps rapping at our door, a God who whispers in our ear, do you understand that you are enough? Why can’t you love yourself enough to take better care of yourself? Will you go on forever holding that grudge, can’t you let go? Don’t you see that when you forgive you set two prisoners free, and one of them is you? Do you understand that I have made you for myself, that there’s a God-shaped vacuum in your heart that you can never fill with anything but me? I was there to hear your borning cry, I’ll be there when you are old, I was there when you were but a child, with a faith to suit you well; in a blaze of light you wandered off to find where demons dwell; but in the middle ages of your life, not too old, no longer young, I’ll be there to guide you through the night, complete what I’ve begun? And when the evening gently closes in, and you shut your weary eyes, I’ll be there the way I’ve always been, with just one more surprise? (1)

This offering is given to you in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.

(1) These are the lyrics to one of my favorite hymns, which the church often uses as a baptismal hymn, “I Was There to Hear Your Borning Cry.”